As the global Islamic finance market grows at an impressive pace, offshore financial centres (OFCs) are increasingly in demand to help structure sharia-compliant products. Unsurprisingly, offshore law firms are seeing a need for Islamic finance-related services grow as well.

One of the more overlooked developments – and opportunities – in global finance in the past two decades has been the quiet rise of Islamic finance. Based upon ethical precepts of Islam as interpreted by Muslim scholars, Islamic finance is steadily growing in appeal, thanks to some 1.6 billion Muslims around the world.

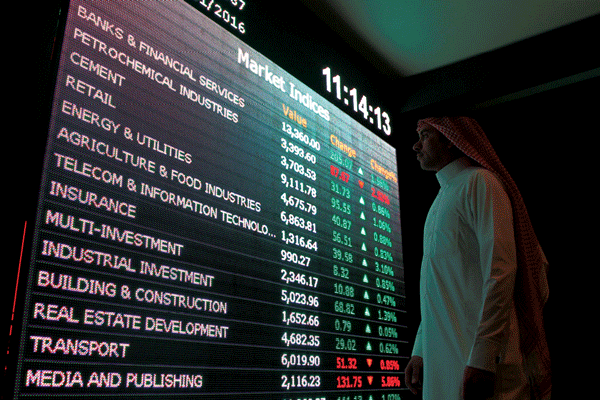

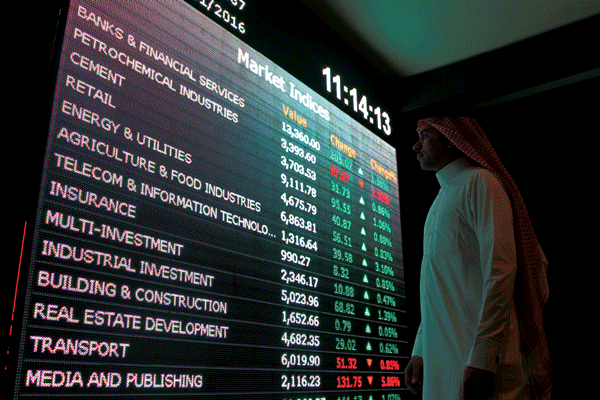

In 2009, total global Islamic finance assets were worth around $900 billion, according to data from the International Shari’ah Research Academy for Islamic Finance. By 2015, that figure rose to more than $2.4 trillion. The global Islamic finance market is expected to exceed $3.4 trillion next year and grow to $5 trillion by 2020.

To say that there is room for further growth in Islamic finance is an understatement. More than $11 trillion in wealth is estimated to be held by Muslim individuals, governments and institutions, over 80 percent of which have been invested in non-Islamic jurisdictions.

The formalisation of centuries-old sharia law, which governs the ways in which Muslims should ethically engage in financial activities, began in earnest in the 1960s with the arrival of the Middle East oil boom. The development of Islamic finance has accelerated in more recent years, with increasingly diverse and sophisticated products and services becoming available in the market.

The often-complicated structuring of sharia-compliant finance vehicles has raised the appeal of offshore finance centres for Islamic financial institutions in recent years. As the offshore finance world has become more involved in Islamic finance, it has been introduced to new terms, concepts and opportunities.

Perhaps the most well-known among these vehicles is the sukuk, which is similar to a bond. Under sharia law, the Western-style interest-paying format is not allowed. Instead, the party which issues a sukuk sells a certificate to a pool of investors, and in turn uses the proceeds of the sale to buy an asset, which is partially owned by the investors. The sukuk issuer is also contractually bound to repurchase the certificate sometime in the future at par value.

Similar to an installment leasing agreement, an ijara is a transaction involving the leasing of fixed assets that return to the lessor after the completion of the lease period. The lease resembles an operating lease, leading to only the partial amortisation of the asset’s value.

Trust financing contracts known as mudaraba – often used as a means for funding Islamic banks – can be used to connect investors with a fund manager or working partner, known as the mudarib. Not long ago, these terms were seldom heard in offshore financial centres. But as OFCs have become more adept at Islamic finance, opportunities for firms capable of providing for the specific needs of Islamic finance clients have grown.

Back to topOFFSHORE’S APPEAL

The appeal of offshore to Islamic financial institutions, as well as individuals and governments, should come as no surprise. Top OFCs offer a world-class financial ecosystem, clear and strong regulatory regimes, protections for both businesses and investors as well as compliance with global standards such as antiterrorism or anti-money-laundering measures. In addition, these jurisdictions provide their services in a discreet manner, providing clients with anonymity.

“The growth in the utilisation of OFCs as platforms for Islamic finance products over the past decade is no coincidence,” says Jeffrey Kirk, managing partner of Appleby’s BVI office. “Whilst the appeal of the OFCs to the architects and underwriters of Islamic finance products has been battered by developments initiated by the OECD and by global regulatory developments over the past few years, the positive environment created by the OFCs to enhance Islamic finance remains in play. It is this environment, strength of financial service professionals resident in those jurisdictions and legacy of success in launching sharia-compliant products that reflect the continuing future positive potential for Islamic finance in the OFCs.”

Fawaz Elmalki, director of the Dubai office of Conyers Dill & Pearman, says that Islamic financing’s recent growth in offshore jurisdictions is driven by a broadening and increasingly sophisticated investor base in key markets, particularly in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. In addition to this expanding investor base, the movement of Islamic finance into the mainstream, including in important Western investor markets such as the UK, is creating momentum for Islamic finance in OFCs, he says.

Anthony Oakes, a partner at Ogier’s Hong Kong office, led the team that in 2015 worked on Garuda Indonesia’s $500 million sukuk. According to Oakes, who also heads the firm’s finance practice in Asia, the synergies of OFCs and the special purpose vehicles that are often applied to Islamic finance are boosting demand for offshore services within the world of Islamic finance. “In many Islamic financing transactions, including sukuk, wakalah and ijara, a special purpose vehicle is used as the issuer of the debt securities,” Oakes says. “A special purpose vehicle set up in an OFC fits the purpose well – given that the SPV can be set up quickly [and] at little expense. And there are experienced service providers who can maintain the SPV and provide legal advice and opinions.”

Islamic funds, or funds that only invest in industries that comply with sharia principles, are a popular form of pooled investment, with funds often formed in OFCs for similar reasons as for establishing SPVs, Oakes adds.

Islamic investors have already developed preferences for offshore activity, Elmalki notes, with many of the traditional OFCs proving popular. “Due to their tax neutrality, political stability and modern legal systems, the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and Mauritius offer flexibility, certainty and a track record that [are] particularly attractive to the Islamic investor base,” he says.

For listed sukuk issued by Middle East issuers, Elmalki says he continues to see the Caymans as the preferred jurisdiction for incorporation of the orphan SPV issuer. “This owes in part to the flexibility, robust corporate laws and judicial system of the Cayman Islands, including hundreds of years of English case law,” he says. “It also reflects the fact that the Cayman Islands has a significant track record in this field, and many sukuk issuances are repeat issuances utilising a tried-and-tested structure that is familiar to investors, issuers, legal counsel and bookrunners alike.”

Conyers recently advised DP World on the establishment of a $3 billion sukuk program to be listed on NASDAQ Dubai and the London Stock Exchange, using a Cayman Islands issuer. On the banking side, Elmalki says Conyers regularly advises Bermuda, BVI, Caymans and Mauritius companies or parties to murabaha and ijara facilities in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) as well as African and Asian transactions, in addition to London property acquisitions.

Ogier’s Oakes also notes the strong appeal of the Caymans for Islamic finance. “The special purpose vehicles used as issuer in sukuk, wakalah and ijara structures tend to be Cayman-exempted companies that are set up as ‘orphan’ SPVs,” he says. “The SPV is referred to as an ‘orphan’ because the beneficial interest in the shares of the SPV, rather than being held by a parent company, is held by a trustee.”

That trustee is either pursuant to a charitable trust of Cayman STAR Trust, Oakes says. A STAR Trust is a trust created pursuant to Cayman statute. Moreover, the Caymans is one of the most popular jurisdictions in the world for establishing funds, so it is a natural choice for setting up Islamic funds, he added.

One of the ways in which the Caymans has secured a leading role in offshore Islamic finance is by reaching out to the industry, says Tahir Jawed, managing partner of Maples and Calder’s Dubai office.

“The Cayman Islands has engaged with the Islamic finance world to pass legislation to clarify the regulatory status of Islamic finance products, particularly sukuk, and provides an efficient and economical platform for investment funds,” Jawed says.

Back to topDRIVING DEMAND

The Islamic world is large and diverse, so it should come as no surprise that the sources of demand for Islamic finance in OFCs are also quite varied. Just as unsurprising is that a large amount of demand for such services comes from the Middle East, the region in the Islamic world where the largest amounts of wealth have been concentrated for the longest amount of time.

“The traditional market of the Middle East remains strong,” says Oakes. “In Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia have also been good markets.” Oliver J. Simpson, an associate at Conyers’ Dubai office, notes that the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, particularly the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, are key markets for offshore sukuk and other Islamic SPV entities.

“This is a reflection in part of their emerging market status and the diverse investor base for these products,” Simpson says.

Large Muslim populations are not a prerequisite for Islamic financing, and its special characteristics are proving attractive to a growing number of markets with relatively small Muslim communities.

“In Asia, we have seen issuers in non-Islamic countries show an interest in accessing the Islamic capital markets and hence arranging Islamic financings,” says Oakes. “For example, the Hong Kong government issued sukuks in 2014 and 2015.”

While the cost of arranging an Islamic financing is typically higher, by accessing a wider pool of funds, the borrower may be able to achieve a lower interest rate, he says. Islamic financings also tend to attract more publicity, he adds.

Back to topA GROWING RANGE OF PRODUCTS

As mentioned above, there are a number of different sharia-compliant products and modes of financing within Islamic finance. There is little doubt that, at least for the moment, sukuk is the core product in the Islamic finance world.

“Sukuk provide secure fixed income investments for sharia-compliant investors and an opportunity for sharia-compliant and conventional corporations and banks to raise finance,” says Jawed of Maples and Calder. “Sharia-compliant investment funds also remain popular as a platform to diversify investments.”

In recent years, investment funds have also provided important funding for small and medium business in the Islamic world. A more recent development has been the use of derivatives by sharia-compliant institutions and this has presented another opportunity for the offshore centres as they have long provided a convenient domicile for hedging and netting arrangements, Jawed adds.

There is, of course, more to Islamic finance than just sukuk. And there is plenty of work being done to accommodate demand for all of these products and services.

“As the Islamic finance market grows and matures, our jurisdictions are being used to facilitate the structuring of Islamic finance products and transactions such as sukuk, ijara, mudaraba and musharaka [as well as] the establishment of sharia-compliant investment funds including real estate, infrastructure and equities funds,” says Elmalki of Conyers.

Listed sukuk – typically issued by an SPV issuer incorporated in the Cayman Islands – remain a mainstay of the Islamic debt capital markets. This is particularly the case where lower oil prices have caused Middle East public companies to look to the capital markets for finance. It may also be because this is increasingly seen as a mainstream product and forms part of the diversified portfolio of many institutional investors.

As elsewhere in finance, things are constantly changing in Islamic finance, and in some cases, individual markets are the drivers of change. “Traditional products – like sukuks – remain popular,” says Ogier’s Oakes. “However, there are new variations of these products, such as, in the Iran market, Islamic securities known as ‘salam sukuk’. The salam contract is basically a financing contract in sharia and these are being used in corporate fundraisings.”

Banks are also developing more sharia-compliant retail and corporate banking and trade finance products, he notes.

Back to topADAPTING TO MARKET NEEDS

Sharia principles may be relatively new to OFCs, but there has been plenty of movement in recent years to accommodate these once-unfamiliar guidelines, with the Caymans leading the way. “In the Cayman Islands, corporate law is famously flexible and business-friendly, enabling companies such as sukuk SPV issuers and others to enshrine the adherence to Sharia principles and investment criteria directly into their constitutional documents,” says Simpson.

Courts in the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, the BVI and Mauritius are familiar with handling cases where sharia plays a role, Simpson notes. “This is important, as the courts may be required to uphold a fatwa from a sharia board that a contract complies with sharia,” he says. “These jurisdictions have a legal system based on English common law and have final recourse to the English Privy Council.” Additionally, Cayman and BVI companies can have an additional name in Arabic, which is also attractive for Islamic parties.

Oakes notes that the flexibility, efficiency and low cost of OFCs are helpful in structuring Islamic financing transactions.

“The legal systems of OFCs are typically based on English law – a trusted and familiar legal system,” he says. “Where the legal systems of OFCs diverge from English law, the rationale is typically to facilitate and provide confidence around financial transactions.”

For example, in OFCs, there is often no restriction on a company giving financial assistance for the purposes of the acquisition of its own shares. This flexibility and the absence of taxation make the structuring of Islamic financing transactions quicker and easier.

Jawed also cites the appeal of the low cost and efficiency – and low tax rates – of OFCs as appealing factors for sharia-compliant transactions. In addition, Islamic finance’s focus on assets gives OFCs another advantage.

“Sharia compliant investments often involve the transfer of assets and the OFCs provide a secure legal framework to transfer assets, create security and uphold contracts,” he says. “Efficient regulation is also important and the Cayman Islands has led the way by introducing legislation to facilitate certain types of Islamic finance transactions.”

The Cayman Islands has engaged with the Islamic finance world to pass legislation to clarify the regulatory status of Islamic finance products, particularly sukuk, and provides an efficient and economical platform for investments funds, adds Jawed.

Back to topGOING FORWARD

There is no doubt that Islamic finance will only play a bigger role in OFCs going forward. So in what direction do those working in this field see things heading? “The Middle East continues to provide the largest market for Islamic finance clients — as wealth and investment activity grows in the region, we anticipate that it will prove an even more important market for the offshore finance centres,” says Jawed. “We anticipate a steady growth in Islamic finance transactions in the OFCs as the Islamic finance market continues to grow and develop. In recent years, we have seen growth in Investment funds, sukuk structures and derivative transactions which utilise OFCs.”

Simpson says he sees the establishment of a growing number of project-oriented entities in the near term. “Islamic banks are typically incorporated in their home jurisdictions – many are wholly or partly state-owned,” he explains. “However, many incorporate offshore entities for specific projects such as sukuk issuances. This trend is likely to continue as the flexibility, track record and dependability of leading offshore financial centres such as the Cayman Islands will remain attractive.”

Demographic trends in countries with non-majority Muslim populations are likely to expand the footprint of global demand for Sharia-compliant financial products and transactions, observes Simpson. “We expect that, with significant Muslim minority populations in certain European countries – particularly the United Kingdom and France – we will see Islamic banking represent an increasingly important portion of the banking sector. We note the UK was the first non-Muslim country to issue a sovereign Islamic sukuk and suspect this trend will continue.”

While the Caymans is expected to maintain its prominent role as an offshore centre for Islamic finance, Simpson says that Mauritius was moving up in this sector. “Islamic finance in Mauritius is on the upswing, with many exciting developments in the Mauritian financial services sector,” he says. “Mauritius is well-known for its numerous double-taxation avoidance agreements with African and Asian countries.”

In 2011, Century Banking Corporation (CBC) was the first Islamic bank to start operations in this jurisdiction, which has a significant Muslim population. In 2014, Habib Bank launched its Islamic banking business through a window operation, alongside its existing banking business. Taken together, these observations point to an increasingly sophisticated and varied engagement between OFCs and Islamic finance. In many ways, this appears likely to create a virtuous cycle, in which greater choice for individuals, companies, Islamic finance institutions and governments attracts more money from non-Islamic jurisdictions, thus providing greater incentive to develop new sharia-compliant products and vehicles to appeal to a growing market.

In addition to offshore finance centres changing to meet the needs of Islamic finance, there are also questions about whether Islamic finance will potentially change in response to OFCs.

“It will be interesting to see whether the Islamic market moves with the developments in the law of the OFCs,” says Oakes. “For example, in 2016, Cayman passed legislation created a new class of Cayman entity – a limited liability company. It will be interesting to see whether LLCs are used in Islamic financing transactions or as the vehicle for Islamic funds in the future.”

This is certainly a possibility. Despite being based on ancient principles – some of which date back as far as the seventh century – Islamic finance is constantly evolving. A recent example of this is the new sharia-compliant gold standard by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI). The new standard went into effect in December 2016, opening up gold investment beyond coins and bullion via an internationally recognised standard for application to gold savings plans, physically-backed gold ETFs, gold mining equities and more.

Should those who set guidelines and standards for Islamic finance continue to take advantage of the opportunities within further clarifications which allow the rest of the global finance system, including OFCs, to engage this massive market on a deeper level, it is safe to say that the golden age of offshore Islamic finance has only just begun.

Back to top